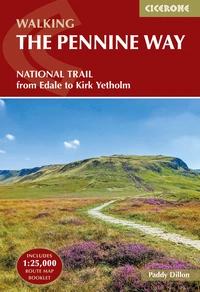

The Pennine Way: everything you need to know

The Pennine Way traverses the 'backbone of England', passing through three national parks and a huge Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It's Britain's oldest National Trail and makes for a long, challenging and very rewarding walk, however it can be adapted to suit walkers of all abilities and is still viewed by many as the ultimate National Trail. Here's everything you need to know about the route.

Essential facts:

What? Britain's oldest long-distance footpath

Where? Some of the most wild and remote upland terrain in England

Start point? Edale in Derbyshire

End point? Kirk Yetholm in the Scottish Borders

Distance? 427km (265 miles)

Cumulative ascent? 11,225m (36,825ft)

Completion time? 2-3 weeks

Why this route? Unspoilt scenery, wild moorland, dramatic geology

How fit do I need to be?

The Pennine Way is the toughest of the National Trails, so it suits those with previous long-distance walking experience. If you have no such experience then you should consider gaining some before you go. Try a weekend walk here and there, staying overnight on your route. Progress to a week-long walk, preferably in upland terrain, carrying everything you would expect to carry on a long trek. Keep a check on your progress day by day and hour by hour, so that you know how long it takes you to cover varying distances and awkward terrain.

What time of year should I walk the trail?

The Pennine Way is naturally busiest in the summer months, when most people take their longest holiday of the year. This is a fine time to walk, as all facilities and services are available, and the weather is generally warm and sunny, with plenty of daylight hours. In August, when the heather moors are flushed purple, fields are in flower, the boggy bits are drier underfoot and the blue sky is flecked with little clouds, the Pennine Way seems perfect.

Spring and autumn can feature many fine days, and both seasons have their own particular charms. Spring sees the gradual greening of the landscape and the first flowers of the year, while newborn lambs bleat plaintively in the lower pastures. Autumn sees the gradual ripening of seeds, hedgerow fruits at their best and cultivated crops ready for harvesting. The days, however, are notably shorter and there may well be cooler, wetter weather.

Winter can be severe in the Pennines, especially when rare falls of deep snow blanket the path and make route-finding particularly difficult. While winter traverses of the Pennine Way are rare, those walkers possessing the skills and stamina to complete the trek also have to cope with the fact that some facilities and services are absent. The hardiest walkers of all are those who aim to be self-sufficient and backpack the route in the winter months.

Is the route waymarked?

The Pennine Way is a designated right of way from start to finish; therefore it should be open at all times and always be free of obstructions. The route is made up of public footpaths, public bridleways, public byways and public highways. SIgnposts usually include the works 'Pennine Way', along with the official National Trail 'acorn' symbol. Marker posts generally feature only the acorn symbol and a directional arrow. Following the 'acorn symbol' is fairly fool-proof, but bear in mind that the Pennine Way intersects with the Pennine Bridleway on a handful of occasions, and also runs concurrent with a considerable stretch of the Hadrian's Wall path. As all these routes are National Trails, they all bear the 'acorn' symbols, and some walkers do find themselves following the wrong trails! There are also some stretches that have no signposts or markers, and this is the policy for what is after all a tough and often remote long-distance trail.

What accommodation is available?

The Pennine Way has plenty of accommodation options, but they are unevenly spaced and in some places may be limited to a single address. Available options throughout the route include hotels, B&Bs, hostels, bunkhouses, campsites and shelters.

Are luggage transfers available?

A handful of companies offer accommodation booking and baggage transfer along the Pennine Way. They might appear expensive, but many walkers are willing to pay the price for someone else to make all their arrangements. It's interesting to note that sometimes, when a number of wayfarers have booked through different companies, the same van collects and delivers all their bags.

Route highlights?

The way passes through the verdant Yorkshire Dales National Park, then crosses the bleak and remote North Pennines. Not content to finish there, it then traverses Hadrian’s Wall and runs through the Northumberland National Park. High in the Cheviot Hills, it finally steps over the border into Scotland to finish at Kirk Yetholm. Highlights include Kinder Scout, Malham Cove, High Cup and Hadrian's Wall.

How do I travel to the start and end points?

Most railway lines and bus routes cross the Pennines from east to west and vice-versa, and only a few routes run parallel to the Pennine Way. Getting to and from the route is reasonably straightforward, but using public transport to get ahead by a stage or two can be quite awkward. Most stages have some form of public transport, but it varies from regular daily services, to one bus per week, and sometimes there is nothing at all, so local taxis or minibus services may be necessary.

What are the Pennine Way stages?

Our guidebook gives a detailed description of the official National Trail route, split into 20 stages with some optional variants. The main stages are detailed in the route summary table below.

| Stage | Locations | Distance | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Edale to Torside | 25.5km (16 miles) | 8hrs |

| 2 | Torside to Standedge | 21km (13 miles) | 6hrs 30min |

| 3 | Standedge to Callis Bridge | 24km (15 miles) | 7hrs 30min |

| 4 | Callis Bridge to Ickornshaw | 25.5km (16 miles) | 8hrs |

| 5 | Ickornshaw to Gargrave | 18km (11 miles) | 5hrs 30min |

| 6 | Gargrave to Malham | 10.5km (6.5 miles) | 3hrs |

| 7 | Malham to Horton in Ribblesdale | 23.5km (14.5 miles) | 7hrs 15min |

| 8 | Horton in Ribblesdale to Hawes | 22km (13.75 miles) | 7hrs |

| 9 | Hawes to Keld | 20km (12.5 miles) | 6hrs 15min |

| 10 | Keld to Baldersdale | 23km (14.25 miles) | 7hrs |

| 11 | Baldersdale to Middleton-in-Teesdale | 10.5km (6.5 miles) | 3hrs |

| 12 | Middleton-in-Teesdale to Langdon Beck | 14km (8.75 miles) | 4hrs 15min |

| 13 | Langdon Beck to Dufton | 21km (13 miles) | 6hrs 30min |

| 14 | Dufton to Alston | 31.5km (19.5 miles) | 10hrs |

| 15 | Alston to Greenhead | 27.5km (17 miles) | 8hrs 30min |

| 16 | Greenhead to Housesteads | 17km (10.5 miles) | 5hrs |

| 17 | Housesteads to Bellingham | 22.5km (14 miles) | 7hrs |

| 18 | Bellingham to Byrness | 25km (15.5 miles) | 8hrs |

| 19 | Byrness to Clennell Street | 23km (14.25 miles) | 7hrs |

| 20 | Clennell Street to Kirk Yetholm | 22km (13.75 miles) | 7hrs |

| Total | - | 427km (265.25 miles) | - |

And finally, a note from our guidebook's author...

Of all the many guidebooks I have written this one is the most personal. The Pennine Way is intricately bound up with my family history. I was born and raised only 6 miles from the Pennine Way and the route was opened when I was only seven years old. My family included some staunch walkers who used to talk about it from time to time. One of them went and walked it, returning with tales to inspire others. As young teenagers, a friend and I stumbled across a Pennine Way signpost on the moors and wondered how long it might take us to walk to Scotland. Soon afterwards, a chance copy of Alfred Wainwright’s Pennine Way Companion, laid it all out for me in black and white.

I could have walked the Pennine Way at the age of 16, but I chose to follow it northwards only as far as Cross Fell, then making a beeline for the Lake District, exploring for a week and walking home via the Yorkshire Dales. I finally walked the whole route for the first time when I was 21, and it snowed for the first five days!

Throughout the 1970s, if you told anyone you were a keen walker, they would ask, ’And have you walked the Pennine Way?’ And anyone actually walking the route might have been asked, ’Are you walking the Pennine Way, or just walking for pleasure?’, as if the two were mutually exclusive! The route was regarded, rightly or wrongly, as something that every ’proper’ walker should aspire to, generating something of a backlash, with some people vowing never to set foot on it.

One thing became painfully obvious throughout the 1970s: the Pennine Way was being trodden to death. Although I always enjoyed walking parts of the route, it was distinctly unpleasant to wade through the mud, occasionally plumbing waist-deep bogs, where the peat had been trodden into the consistency of cold, black porridge. Apart from occasional forays during the 1980s, I left the route well alone while the problems of over-use and erosion were addressed, ultimately by completely rebuilding several stretches of the trail.

Once everything had bedded down and grassed over I renewed my acquaintance. It was worth the wait, and as the years roll by, the stone-paved paths will become as much a part of the Pennine Way as the centuries-old packhorse ’causeys’ that preceded it. The scenery remains the same as ever and only the conditions immediately underfoot have changed, and for the better.

Sadly, the Pennine Way is no longer held in the high regard it enjoyed at the outset. Today’s walkers have other National Trails to choose and infinite opportunities to walk challenging trails abroad. This is well and good, but the Pennine Way remains the toughest of the National Trails, one that every long-distance walker should aspire to.

Long may it enjoy a future as part of Britain’s outdoor heritage.

Paddy Dillon

More Information:

The Pennine Way Association

The Pennine Way - the Path, the People, the Journey

£12.95

A portrait of the The Pennine Way, Britain's oldest and best known long-distance footpath, stretching 268 miles from the Peak District to the Scottish Borders. This personal, thoughtful and often humorous story of the path's remarkable history, includes the experiences of walkers and local characters on this exhilarating and complex path.

More informationThe National Trails

19 Long-Distance Routes through England, Scotland and Wales

£18.95

This inspirational guidebook details the UK's 19 National Trails, offering stage by stage overviews for each route including the popular South West Coast Path, Hadrian's Wall Path, Pennine Way, West Highland Way, Cotswold Way, Offa's Dyke Path, South Downs Way, Southern Upland Way and many others.

More information