Everything you need to know about the England Coast Path

The England Coast Path is VERY, VERY LONG by any measure. In the UK it will dwarf all the existing National Trails, long distance paths and established long distance walking challenges. Here's what you need to know...

Great Walks on the England Coast Path

30 classic walks on the longest National Trail

£20.00

SALE

£16.00

Guidebook to 30 routes celebrating the best day and weekend walks on the England Coast Path, a new National Trail. Includes a varied selection of walks along the country's diverse shoreline, on cliff paths, estuaries, beaches and saltmarsh. Routes from 9 to 45km to suit all ages and abilities, many of which can be enjoyed all year round.

More information

What is the England Coast Path?

Well, it's a way of walking round the whole of England. This makes it the longest continuous coastal trail in the world!

The whole of England! How long is the path?

The total length of the England Coast Path National Trail will be 4,400km or 2,700 miles.

How does this compare to other National Trails?

When complete, the England Coast Path will be longer than all the other 15 National Trails combined (they total around 4,000km or 2,500 miles).

- For reference, the longest National Trail is currently the South West Coast Path at 1,014km (630 miles).

- The Pennine Way comes in at a paltry 435km (268 miles).

- The Offa’s Dyke Path is a mere 285km (177 miles).

- The Wales Coast Path is 1,400km (870 miles).

- The Land’s End to John o’Groats walk is anything from 1,407km (874 miles) on roads to 1,956km (1,215 miles) by paths.

- The Cambrian Way from Cardiff to Conwy is 479km (298 miles).

- The Southern Upland Way across Scotland is 344km (214 miles).

- Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk is 292km (182 miles).

Why is this trail important?

Britain's an island shaped by the sea and most Brits live within 70 miles of the ocean. The Coast Path will boost tourism, connect communities, improve health, and let everyone enjoy the English seaside. It's about accessing, appreciating, and enjoying our natural and maritime heritage.

What else is this trail known as?

In honor of His Majesty King Charles III's coronation, the England Coast Path has been renamed the 'King Charles III England Coast Path', creating a lasting legacy for walkers along the entire English coastline.

It's a world-beating path...

Outside the UK there are plenty of super long walking trails that are certainly wilder and more remote and arduous, from the Pacific Crest and Appalachian Trail in the USA to the Hokkaido Nature Trail in Japan; from the Grand Italian Trail the length of Italy and the Way of St James (Camino de Santiago de Compostela) in northern Spain. However, the England Coast Path will be the longest coastal walking trail anywhere in the world. The GR34 along the Brittany coast in north west France comes in at 1,700 km (1,100 miles); and the Lycian Way provides a 540 km (340 mile) trail around the south coast of Turkey, but it will be the first time EVER that a country has a coastal walking trail around its entire seaboard.

And, if you add the Wales Coastal Path, you will be able to continuously walk 5,899km or 3,665 miles around the entire coast of England and Wales from Gretna Green all the way round to Berwick upon Tweed. So how about a path around Scotland next…?

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

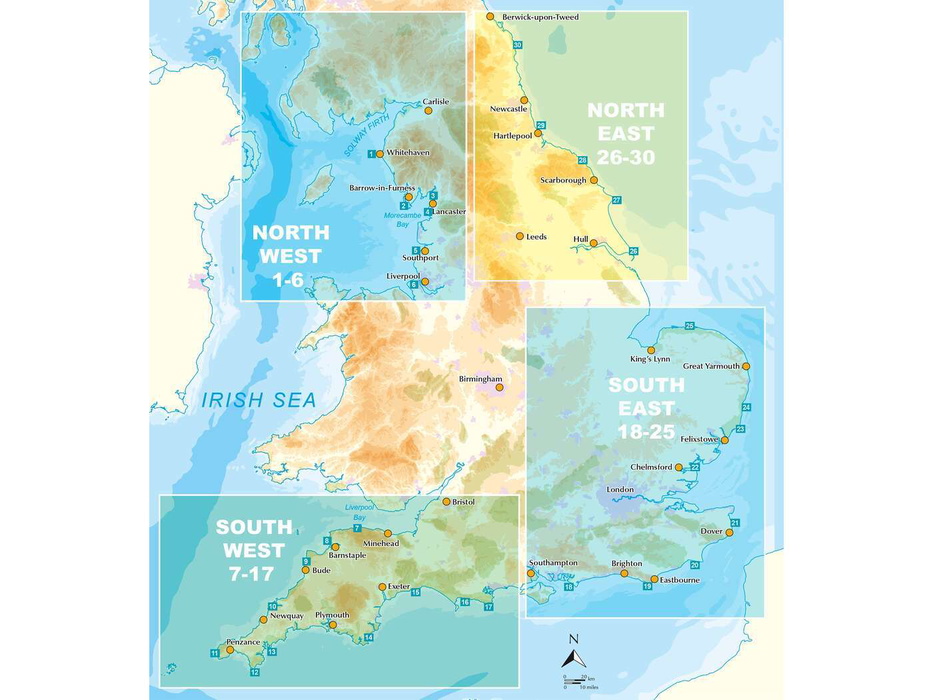

| North West | From the Scottish border near Gretna Green down to the Welsh border near Chester, this coastal stretch offers a diverse journey, traversing the wilderness of the Lake District, the excitement of Blackpool, and the vibrant urban culture of Liverpool. |

| North East | From the Scottish border above Berwick to the Wash, this coastline is renowned for its beaches, castles, and seaside holiday resorts. However, there's much more to discover, including quaint fishing villages nestled in sheltered coves and rugged cliffs hosting vast seabird colonies. |

| East | From the Wash to the Thames Estuary, the journey unveils breathtaking wildlife and rich cultural experiences. Discover sand dunes, market towns, and villages, all set against stunning seascapes, perfect for solitary exploration, companionship with a canine friend, or family outings. |

| South East | From the Thames Estuary to Bournemouth, this coastal stretch is massive. It includes typical seaside towns with piers, beach huts, and amusements, as well as long empty beaches and nature reserves for peace and quiet. There's something for everyone here. |

| South West | From the Welsh border at Chepstow to Bournemouth, this section of coastline follows some of the most breathtaking views. Connecting coastal resorts, towns, and villages, it leads you along cliff tops, to the edges of promontories, across piers and promenades, and along estuaries. |

Great Walks on the England Coast Path

30 classic walks on the longest National Trail

£20.00

SALE

£16.00

Guidebook to 30 routes celebrating the best day and weekend walks on the England Coast Path, a new National Trail. Includes a varied selection of walks along the country's diverse shoreline, on cliff paths, estuaries, beaches and saltmarsh. Routes from 9 to 45km to suit all ages and abilities, many of which can be enjoyed all year round.

More information