Climbing K2: Jake Meyer's ten-year journey to the summit of the savage mountain

Jake Meyer, one of the youngest Britons to climb Everest, and the youngest man in the world to complete the Seven Summits, undertook his biggest challenge when he faced The Savage Mountain, K2.

The Savage Mountain

K2, the infamous ‘Savage Mountain’ of the Karakoram, is one of the world’s most formidable mountaineering challenges. With a death-to-summit ratio once as high as 1 in 4, only around 400 climbers have ever reached its summit — fewer than have travelled to space — while 85 have died trying.

Unlike Everest, which sees hundreds of ascents annually (over 700 in 2018), K2 goes unclimbed in around 40% of years. Its steep, technical mixed rock and ice routes are far more demanding, and even the so-called ‘easiest’ slopes are swept by colossal avalanches and barraged by constant rock and ice fall.

Camp sites offer little comfort: tents are often pitched at precarious angles, sometimes hanging partially over sheer drops. Its northerly location also brings harsher, more unpredictable weather, with just one or two viable summit days in many years.

Throughout my teenage years, my dream was always to climb the Seven Summits. As I set out to scale the highest peak on each continent, it became the singular focus of all my energy and effort.

When I reached the summit of Everest on 4 June 2005, aged 21 years and 134 days, I was overwhelmed by a surge of emotions — relief, elation, and utter exhaustion. Yet, amid the euphoria, I also felt an unexpected hollowness — a sense of fulfilment laced with emptiness. Like an addict crashing after a final fix, I was gripped by the question: What next?

I had climbed as high as it was possible to go. Everest was the hardest thing I had ever done — but I couldn’t help wondering whether there was an even tougher test waiting at high altitude. And without hesitation, I knew there was only one mountain that fit that description: K2 — the world’s second-highest and most savage peak.

Just reaching K2’s base camp requires a gruelling 120km trek along one of the longest glaciers in the world, with every item of equipment and supply carried by porters or mules. On our most recent expedition, we employed over 240 porters to support our seven-week stay on the mountain.

Preparing for K2: trials before the summit push

I was first set to attempt K2 in 2008, but a sponsor pulled out at the last minute and I was forced to cancel the trip. At the time I was devastated — but that frustration soon gave way to relief. That season turned into one of K2’s deadliest, with 11 climbers losing their lives in the space of just 48 hours.

It wasn’t until 2009 that I was finally able to make an attempt, joining an American-led international team. We approached via the lesser-climbed Cesen route and spent eight weeks fixing thousands of metres of rope by hand, preparing for a summit push in early August. But by the time we reached the upper slopes — just hours from the top — we found them dangerously loaded with deep powder snow. Not only was it exhausting to climb through, it posed a serious avalanche risk. Knowing that it’s better to be a live donkey than a dead lion, we made the difficult but ultimately obvious decision to turn back and abandon the summit bid.

K2 took a back seat for several years — an operational tour in Afghanistan, the start of a career in management consultancy, and the arrival of a young family all demanded my attention — but the mountain never left my thoughts. It remained a constant dream, quietly waiting. In 2016, a mix of luck and timing opened the door once again. I was offered a place on a British team attempting the Abruzzi Ridge — the first British expedition on K2 since 2004.

As before, we spent weeks rotating up and down the mountain, climbing a little higher each time to build our acclimatisation, before retreating to base camp to rest and wait out the frequent storms. Eventually, a break in the weather offered a rare opportunity — and we committed to a summit push: a five- to six-day round trip to the top of the world’s most savage peak.

While climbing with the Sherpa fixing team, our third camp at 7300m was struck by a massive avalanche that completely destroyed it and swept around $200,000 of rope, oxygen and equipment off the side of the mountain. This (and some other factors) led to us having to once again abandon our summit attempt and return dejected, but lucky to be alive, back home.

Climbing K2 in 2018: from Broad Peak acclimatisation to final camp

A third attempt naturally drew the inevitable ‘third time lucky’ comments. With rising expedition costs, another two months away from work and family — including my two young daughters — there was a real hope that this would finally be the one. This time, I teamed up with a Slovenian climber and three Nepalese Sherpas, sharing basecamp with a team attempting K2’s neighbour, Broad Peak — itself one of the formidable 8000m giants.

Having already spent ample time on K2’s lower slopes, I chose to minimise time on the Savage Mountain itself, doing all my acclimatisation rotations on Broad Peak instead. I even made a solo summit attempt there, reaching 7,900m, which set me up well for the push on K2. Thankfully, we planned only a single summit push this time.

The route remained as steep and challenging as ever, with no signs of easing after all these years. The reduced snowfall made some sections easier to climb, but it also increased the risk of rockfall. Though a fixing team was busy securing ropes, climbers had to use them cautiously and avoid over-reliance. Tragically, a Canadian friend — who’d been on the mountain with me in 2016 — was abseiling a steep section when his rope snapped, resulting in a fatal fall of nearly 2,000 metres.

Our small team of five climbed alongside a larger group, which helped us break trail and fix ropes higher up. After a rest day — and waiting out bad weather — at Camp 3 (7,350m), we established a temporary Camp 4 at 7,650m before beginning the final 1,000-metre vertical climb to the summit.

K2 summit attempt

We set off for the summit at 10:30pm, aiming to complete most of the climb under the cover of darkness. The cold night air keeps snow, ice, and rock more consolidated, making the climb safer. It’s also crucial to summit early in the day, allowing enough daylight to descend safely — many climbers on K2 and other peaks have been lost or seriously injured trying to descend after dark.

The route took us onto K2’s shoulder, where the gradient eased briefly for a few hundred metres before becoming brutally steep alongside the infamous ‘Bottleneck’ — a narrow, 70º snow funnel beneath a huge, overhanging ice cliff known as a serac. This serac famously collapsed in 2008, killing several climbers instantly and cutting ropes for those stranded above. Thankfully, it remained solid this time, though its ominous presence was hard to ignore. We carefully traversed a narrow, tentative path around and beneath it.

Next came an incredibly steep, solid ice wall, which we climbed painstakingly using the front points of our crampons and ice axes. From there, we joined the slightly more generous summit ridge, which would lead us to the top. At 8:00am local time — after 9.5 hours of climbing and with the sun beginning to warm us in our down suits — we reached the crest of the summit ridge. Suddenly, the ice sloped away in every direction: we had reached the summit.

It’s difficult to capture the moment in words. Like Everest, it was a flood of emotions — hugging and celebrating with fellow climbers, savouring the breathtaking views, juggling sponsor duties like banners and photos, and staying vigilant about oxygen supplies and the simple yet crucial task of keeping your gloves on. In the end I spent around 45 minutes on the summit, before deciding that it was probably time to head back down.

Descending K2: the most dangerous part of the climb

Without wanting to be melodramatic, it is almost more important to keep your wits about you on the descent as it is going up. Of the four Brits to have died on K2, three of them died on the decent, having made it to the summit. While they might have been caught in bad weather, or other tragic factors, it is all too easy to make silly mistakes while abseiling or changing ropes (a Japanese climber would die the day after when he fell while descending from the summit), or to let exhaustion overwhelm you.

While the descent was incredibly gruelling, the five of us (and the rest of the larger team) managed to return safely to camp 2 (c6500m) and, the following day, return exhausted but elated to base camp. It felt like once we were back in the comparative safety of base camp, we could finally relax, and it was only then that we could allow the enormity of what we’d just achieved to sink in.

They say that to climb Everest, you need conditioning, but to climb (and survive) K2 you need heart. Well, the last 10 years have required plenty of heart – and an unerring sense of determination, tenacity, sacrifice, stubbornness and a little bit of luck.

Three times I’ve trekked 120km up the Baltoro Glacier in search of satisfaction. Twice I’ve trekked 120km back defeated, broken but alive. Churchill is purported to have said: ‘Success is not final, failure is not fatal. It is the courage to continue which counts.’ Thankfully, there appears to be some truth in the old adage ‘third time’s a charm’.

Of course now, having finally reached the top of K2 (and returned safely), I’ve once again found myself putting one challenge to bed and immediately searching for the next. Fortunately, the world offers many more mountains and opportunities for many more adventures.

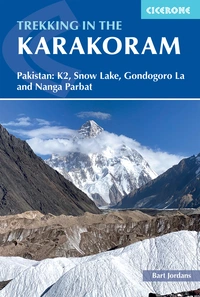

Trekking in the Karakoram

Pakistan: K2, Snow Lake, Gondogoro La and Nanga Parbat

£24.95

SALE

£19.96

Three of the most popular high-altitude treks in Pakistan's Karakoram, among some of the world's highest mountains: Snow Lake and the Biafo and Hispar Glaciers; the K2 Base Camp Trek; and Gondogoro La via Concordia. Also includes two shorter treks in the shadow of Nanga Parbat: Fairy Meadows and Rakhiot Base Camp Trek; and a trek to Diamir Face.

More information