What are the Big Rounds?

The Bob Graham Round, the Paddy Buckley Round and the Charlie Ramsay Round are known to mountain runners as three of the most difficult 24-hour challenges in the world. But whether you run or walk, each round is a long-distance classic.

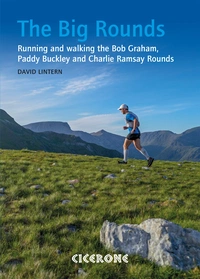

The Big Rounds

Running and walking the Bob Graham, Paddy Buckley and Charlie Ramsay Rounds

£22.95

Guidebook to walking and running the 'Big Rounds' - The Bob Graham, the Charlie Ramsay and the Paddy Buckley. Includes practical information and advice, notes on access and environmental impact, tales from the Rounds, plus insights and strategies from the likes of Jasmin Paris, Nicky Spinks, Charlie Ramsay, Jim Mann and Paddy Buckley.

More informationThe Big Rounds

Collectively, the mainland ‘Big 3’ take in 113 mountain summits (including the highest peaks in England, Wales and Scotland), more than 25,000m (83,000ft) of ascent and nearly 300km (183 miles) across three of Britain’s most distinct mountain ranges – the Snowdonia National Park in Wales, the Lake District National Park in England and a vast area of Lochaber in the highlands of Scotland.

The beauty of the Rounds in my view is the line that each takes. It’s not about just the tops themselves, but the quieter, less visited places in between – so they are a great way to revisit the familiar as well as discover the unknown. As a group, they illustrate the differences in our regional mountain cultures, as well as the rich social and historical links between them. They are also difficult to do and something I aspired to, even as a walker!

The Bob Graham Round - the Lake District, England

8163m (26,778ft) of ascent over 98.78km (61.37 miles) and 42 tops

The Bob Graham visits Skiddaw and Blencathra, then tours the eastern ridge to Helvellyn, ducks across Fairfield to the Langdale peaks before covering the high ground to Scafell Pike, the Wasdale horseshoe to Honnister Pass, before returning to the start point at Moot Hall in Keswick. It can also be traversed in the opposite direction. It was first run successfully by Bob and pacers in 1932, in a time of 23hr 39min, wearing gym shoes and fueled by bread, butter and boiled eggs.

The Paddy Buckley Round - Snowdonia, Wales

8700m (28,750ft) of ascent over 100.5km (62.43) miles and 47 tops.

Otherwise known as the Welsh Classical Round, the line devised by Paddy was first run successfully in 1982 by Wendy Dodds in a time of 25hr 38min. The start can be at any point on the round and it can be taken in either direction, covering Llanberis, the Glyderau, the Carneddau, Siabod and the ‘boundary ridge’ to the Moelwyns, the more solitary ground north of Moel Hebog, as well as the Snowdon massif.

The Charlie Ramsay Round - Lochaber, Scotland

8803m (28879ft) of ascent over 92.83km (57.6 miles), 23 Munros and 1 subsidiary top.

Beginning from the Glen Nevis YHA in July 1978, Charlie expanded the Philip Tranter Round (all the hills around Glen Nevis), first running across the Mamores, down to Loch Treig, over the mountains west of Loch Ossian, across the Grey Corries, before traversing the Aonachs and Ben Nevis. He made it back to the youth hostel with 2 minutes to spare in a time of 23hr 58min. The route can also be taken in the opposite direction.