An Introduction to Offa's Dyke Path

The iconic earthwork of Offa’s Dyke, the longest linear earthwork in Britain, stands as a stunning testament to the determination and skill of its creators, being a defining landscape feature of the Welsh borders.

The long-distance path named after the Dyke is just as outstanding. A magnificent, long but not too difficult walk through the wonderfully diverse and at times remarkably remote countryside of the Welsh Marches, in its middle reaches it follows the Saxon earthwork unswervingly for many miles, Dyke and path together forming an intrinsic feature of the border landscape.

One of the real classics among Britain’s challenge walks, the 285km (177-mile) National Trail offers an unforgettable journey between the Severn estuary and the North Wales coast, conquering mountain ranges, contouring above the Wye and Dee, visiting superb hillforts and Norman castles and exploring the hidden heritage of the Marches.

How long is Offa's Dyke Path?

Offa's Dyke path is 177 miles long (285km). How long does it take? The beauty of Offa’s Dyke Path is that there is no one answer to this question, and individual walkers can adopt a variety of different strategies to suit their interests and circumstances.

The whole trail can comfortably be walked within a fortnight, and so this guidebook is structured around 12 stages that are sometimes long but never particularly arduous. The waymarking is good, the going underfoot is rarely a problem, the days are full of interest and the miles fall away easily. So much so, indeed, that strong walkers might be tempted to complete the walk in 10 days at most.

South to north, or north to south?

It’s worth bearing in mind that while the most popular direction of travel may be from south to north, it’s entirely feasible to make the journey in the opposite direction, possibly into the prevailing wind and the sun but with the compensation of a final day walking above the high limestone cliffs of the lower Wye gorge to Chepstow Castle and the Severn estuary at Sedbury cliffs.

Who was Offa?

Offa became the King of Mercia in 757 and inherited a set of poor defensive ditches designed to protect his kingdom from invasion. Around the time of 780 King Offa organised the strengthening of the existing dykes by making the ditches deeper and piling the earth into high banks. You can find more information at the Offa's Dyke Association website.

Offa's Dyke Path

National Trail following the English-Welsh Border

£17.95

This guidebook describes Offa's Dyke Path National Trail, a 177 mile (283km) long-distance walk along the English-Welsh border between Sedbury (near Chepstow) and Prestatyn. The guidebook is split into 12 stages with suggestions for planning alternative itineraries. With OS 1:25,000 map booklet.

More informationHow hard is Offa’s Dyke path?

This trail is massively adaptable but does involve some parts that require a good level of fitness to complete in one day, meaning it can be as relaxing or as intense as you make it. This flexibility allows people to tackle it at their own pace, we would advise looking into the different stages and evaluating how long you’d like to take on each.

For those seeking still greater challenges, the trail links with the Wales Coast Path at both Chepstow and Prestatyn, offering a 1690km (1050-mile) round-Wales challenge walk of epic proportions; while the trail also intersects with a number of other long-distance routes including the Wye Valley Walk at Chepstow and Hay, the Beacons Way near Pandy, Glyndŵr’s Way at Knighton and Welshpool, and the Clwydian Way from Llangollen northwards

When should you go?

Excellent walking is available in every season, with bluebells carpeting the woodland floors in spring, wildflowers and butterflies in summer, heather moorlands in late summer and the golden hues of the autumn bracken, and the crisp delights of sunny winter days. Bear in mind, though, that the high hills can sometimes be unforgiving in winter conditions, and that daylight hours in winter may be too short to allow the completion of some of the longer stages

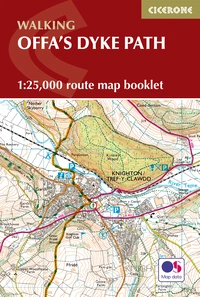

Offa's Dyke Map Booklet

1:25,000 OS Route Mapping

£12.95

Map of the 177 mile (283km) Offa's Dyke Path National Trail, between Sedbury (near Chepstow) and Prestatyn. The trail takes 2 weeks to walk, and is suitable for walkers at all levels of experience. This compact booklet of OS 1:25,000 maps shows the full route, providing all of the mapping you need, and is included with the guidebook.

More informationOffa's Dyke Path Stages

Find a quick summary of the stops recommended in the Cicerone Guide, written by Mike Dunn, alongside a more detailed description of each stage below.

| Stage | Start/Finish | Distance | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sedbury Cliffs - Monmouth | 29km (18 miles) | 7–9hrs |

| 2 | Monmouth - Pandy | 27km (17 miles) | 6–8hrs |

| 3 | Pandy - Hay-on-Wye | 28km (17½ miles) | 7–9hrs |

| 4 | Hay-on-Wye - Kington | 23 km (14½ miles) | 6–8hrs |

| 5 | Kington - Knighton | 23km (14 miles) | 6–7hrs |

| 6 | Knighton - Blue Bell Inn, Brompton Bridge | 24km (15 miles) | 7–9hrs |

| 7 | Brompton Bridge - Buttington | 20km (12½ miles) | 5–6hrs |

| 8 | Buttington - Llanymynech Canal Bridge | 17km (10½ miles) | 4–5hrs |

| 9 | Llanymynech Canal Bridge - Chirk | 22km (13½ miles) | 6–7hrs |

| 10 | Chirk - Llandegla | 24km (15 miles) | 6–8hrs |

| 11 | Llandegla - Bodfari | 28km (17½ miles) | 7–9hrs |

| 12 | Bodfari - Prestatyn Seafront | 20km (12 miles) | 5–6hrs |

Stage 1: Sedbury Cliffs - Monmouth

- Distance: 29km (18 miles)

- Time: 7–9hrs

The first section of Offa’s Dyke Path is also one of the best: indeed, it is widely regarded as one of the classic walks of lowland Britain. The walk requires a good level of fitness since it follows an undulating route on the edge of the Forest of Dean, repeatedly descending towards the Wye and climbing again along ridges high above the gorge, and it may be worth considering tackling the route in two stages, perhaps with a break around Bigsweir.

Stage 2: Monmouth - Pandy

- Distance: 27km (17 miles)

- Time: 6–8hrs

The trail crosses a corrugated landscape of small fields and minor valleys, leaving behind the Wye valley and gradually rising towards the foothills of the Black Mountains. As long ago as the 1870s the predominant land uses were sheep grazing and cider and perry pear orchards, and superficially little has changed. There are few villages and only a scatter of farming hamlets, so there is a surprising feeling of remoteness.

Stage 3: Pandy - Hay-on-Wye

- Distance: 28km (17½ miles)

- Time: 7–9hrs

An exhilarating yet surprisingly easy traverse of the eastern ridge of the Black Mountains, with the Llanthony valley to the west and the Olchon valley in Herefordshire to the east. The 28km (17½-mile) main route requires reserves of stamina, however, and walkers may want to consider breaking the journey in Llanthony or Longtown, and climbing back up to the ridge the following day. In bad weather the low-level route via Llanthony, Capel-y-ffin and the Gospel Pass is a sensible alternative.

Stage 4: Hay-on-Wye - Kington

- Distance: 23 km (14½ miles)

- Time: 6–8hrs

This section of the trail begins with easy riverside walking – a complete contrast to the preceding stage – but it should not be underestimated since it soon rises to cross the rolling border country of western Herefordshire and south Powys. The route lies across Little Mountain and Disgwylfa to the remote hamlet of Newchurch, but a particular highlight is the trek along the outstanding former drovers’ road, Red Lane. The stage ends with a wonderful traverse of the stunning Hergest Ridge, with easy ridge walking and extensive views in all directions.

Stage 5: Kington - Knighton

- Distance: 23km (14 miles)

- Time: 6–7hrs

This is Welsh Marches walking at its finest: not too demanding but full of interest. The scenery is spectacular, with wide-ranging views, and the national trail is reunited with Offa’s Dyke after an absence of more than 80km (50 miles), following long stretches of the very well-preserved ancient monument across remote hill country.

Stage 6: Knighton - Brompton Bridge

- Distance: 24km (15 miles)

- Time: 7–9hrs

This is the toughest section of the trail, with some steep (although reasonably short) climbs and some equally steep descents as the Dyke – superbly preserved in places – heads directly and uncompromisingly across the green hills of south Shropshire, which are unhelpfully aligned from east to west.

Stage 7: Brompton Bridge - Buttington

- Distance: 20km (12½ miles)

- Time: 5–6hrs

The walking on this section of the trail is substantially less challenging than the switchback section through the south Shropshire hills, with a delightfully gentle passage through the historic landscape of the Vale of Montgomery, with big hedged fields and parkland now occupying the floor of a former glacial lake, followed by the traverse of the Long Mountain. Offa’s Dyke Path cuts through a classic high-Victorian estate here, with evidence of some of the innovations that marked out Leighton Park, before climbing to the hillfort of Beacon Ring and descending into the Severn valley at Buttington.

Stage 8: Buttington - Llanymynech Canal Bridge

- Distance: 17km (10½ miles)

- Time: 4–5hrs

The walking on this stage of the trail is very straightforward, marking the transition between the rolling hills of the middle Marches and the slightly sterner North Wales hills that lie ahead. The respite is welcome but the attractions along the route should not be underestimated, with delightful stretches alongside the River Severn and a towpath walk of exceptional ecological and historical interest on the Montgomery Canal.

Stage 9: Llanymynech Canal Bridge - Chirk

- Distance: 22km (13½ miles)

- Time: 6–7hrs

This is a fascinating day’s walking, although it is occasionally difficult to navigate as the route twists and turns through the Oswestry uplands. The waymarking is good, however, and the walking is never difficult, while the variety of landscapes is exceptional.

Stage 10: Chirk - Llandegla

- Distance: 24km (15 miles)

- Time: 6–8hrs

This is a wonderful and extremely varied day’s walking, passing the intact fortress of Chirk Castle and the short-lived, ruined Castell Dinas Bran, crossing Thomas Telford’s world-famous Pontcysyllte Aqueduct (an alternative route caters for those without a head for heights!), skirting below the dramatic limestone outcrops of Trevor Rocks and Creigiau Eglwyseg, and crossing heather moors populated by the elusive black grouse on the way to the mountain-biking mecca of Llandegla Forest and the village of Llandegla.

Stage 11: Llandegla - Bodfari

- Distance: 28km (17½ miles)

- Time: 7–9hrs

The journey along the long, undulating ridge of the Clwydian hills – the narrow range dividing industrial Deeside from rural Denbighshire – is one of the highlights of the entire walk. A near-continuous scarp slope to the west divides the ridge from the Vale of Clwyd, centred on the medieval castles and market towns of Ruthin and Denbigh. The trail uses a succession of green lanes in the Clwydian foothills, rising to the ridge at its central, highest point to visit the iconic Jubilee Tower on Moel Famau, and passing a string of superb hillforts crowning most of the major summits.

Stage 12: Bodfari - Prestatyn Seafront

- Distance: 20km (12 miles)

- Time: 5–6hrs

This final stage of the trail occasionally needs care in route-finding as it twists and turns among the low hills and valleys in the northern part of the Clwydian Range. The walking is easy, however, on lanes and field paths, with an increasingly impressive panorama of Snowdonia and the North Wales coast from the Great Orme to Deeside.

Useful Information:

Offa's Dyke Path Accommodation

The opportunity to take a flexible approach to walking Offa’s Dyke Path depends to a large extent, of course, on the availability of accommodation and other facilities at key points along the way. The National Trails website has some useful suggestions, while a detailed list, updated annually, is compiled by the Offa’s Dyke Association.