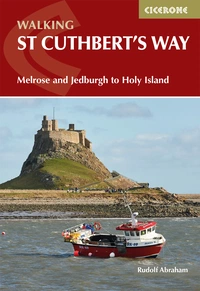

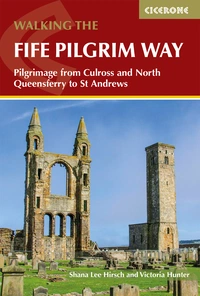

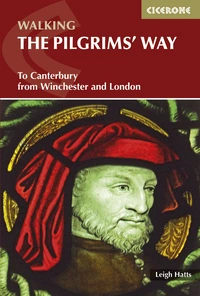

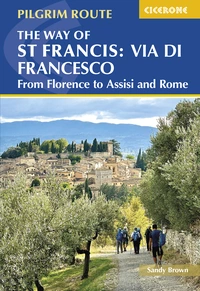

Pilgrim Trails - what you need to know

Historically, pilgrims walked to religious sites as part of both physical and spiritual journeys, and now, these trails have become increasingly popular with walkers who want to travel in the pilgrims' footsteps. From the beautiful towns and villages of Spain to the ancient woodlands and historic remains of the Kingdom of Fife, there are many different pilgrimages across the world. Here, we highlight some of the best pilgrim trails around the world, featuring the classic Caminos as well as other less-known pilgrimages, and provide our go-to resources to plan your next pilgrim adventure.